As scientists and politicians desperately search for medicines to slow the deadly coronavirus, and as President Trump touts a malaria drug as a remedy, a look back to the 1955 polio vaccine tragedy shows how hazardous such a search can be, especially under intense public pressure.

AD

Inside Trump’s embrace of a risky drug against coronavirus

Despite Eddy’s warnings, an estimated 120,000 children that year were injected with the Cutter vaccine, according to Paul A. Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Roughly 40,000 got “abortive” polio, with fever, sore throat, headache, vomiting and muscle pain. Fifty-one were paralyzed, and five died, Offit wrote in his 2005 book, “The Cutter Incident: How America’s First Polio Vaccine Led to the Growing Vaccine Crisis.”

It was “one of the worst biological disasters in American history: a man-made polio epidemic,” Offit wrote.

In those days, polio, or infantile paralysis, was a terror.

“A national poll … found that polio was second only to the atomic bomb as the thing that Americans feared most,” Offit wrote.

Placed in an iron lung, 2-month-old Martha Ann Murray is watched by nurse Martha Sumner at St. Mary's Hospital in Tucson in 1952. (AP) Placed in an iron lung, 2-month-old Martha Ann Murray is watched by nurse Martha Sumner at St. Mary's Hospital in Tucson in 1952. (AP) “People weren’t sure how you got it,” he said in an interview last week. “Therefore, they were scared of everything. They didn’t want to buy a piece of fruit at the grocery store. It’s the same now. … Everybody’s walking around with gloves on, with masks on, scared to shake anybody’s hand.”

“I remember my mother … wouldn’t let us go to a public swimming pool,” said Offit, 69. We “all had to go into one of those little plastic pools in the back so that we wouldn’t be in a public place.”

Everyone wore masks during the 1918 flu pandemic. They were useless.

The worst polio outbreak in U.S. history struck in 1952, the year after Offit was born. It infected 57,000 people, paralyzed 21,000 and killed 3,145. The next year there were 35,000 infections, and 38,000 the year after that.

Many survivors had to wear painful metal braces on their paralyzed legs or had to be placed in so-called iron lungs, which helped them breathe. There was no vaccine and few treatments. (One bogus approach was to spray acid into the noses of children to block the virus. All it did was ruin the sense of smell.)

The polio ward in 1955 at Haynes Memorial Hospital in Boston, where iron lung respirators helped patients breathe. (AP) The polio ward in 1955 at Haynes Memorial Hospital in Boston, where iron lung respirators helped patients breathe. (AP) Often polio victims were children, but the most famous affected American was President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who got polio and was paralyzed from the waist down in 1921 when he was 39.

In 1951, Jonas Salk of the University of Pittsburgh’s medical school received a grant from the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis to find a vaccine. During intense months of research, he took live polio virus and killed it with formaldehyde until it was not infectious but still provided virus-fighting antibodies.

When tests showed that the vaccine was safe, Salk told his wife, “I’ve got it,” Offit wrote.

Word of his success soon leaked out. Public pressure grew for the vaccine and for a large-scale trial.

In 1953, Salk tested it on himself, his wife and three children.

The gutsy — possibly crazy — scientists who risked death testing vaccines on themselves

On April 26, 1954, Randy Kerr, a 6-year-old second-grader from Falls Church, Va., stood in the cafeteria of the Franklin Sherman Elementary School in McLean and became the first to be vaccinated in a massive field study.

Salk’s vaccine was given to 420,000 children. A placebo was given to 200,000. And 1.2 million were given nothing.

The study found that children who did not get the vaccine were three times more likely to be paralyzed with polio than those who received the vaccine.

A year later, on April 12, 1955, when officials announced the results at a news conference at the University of Michigan, there was jubilation. Reporters hollered: “It works! It works!” Offit wrote.

The news made front-page headlines across the country. “People wept,” Offit said. “There were parades in Jonas Salk’s honor. … That’s what contributed to the tragedy of Cutter more than anything else … the irony.”

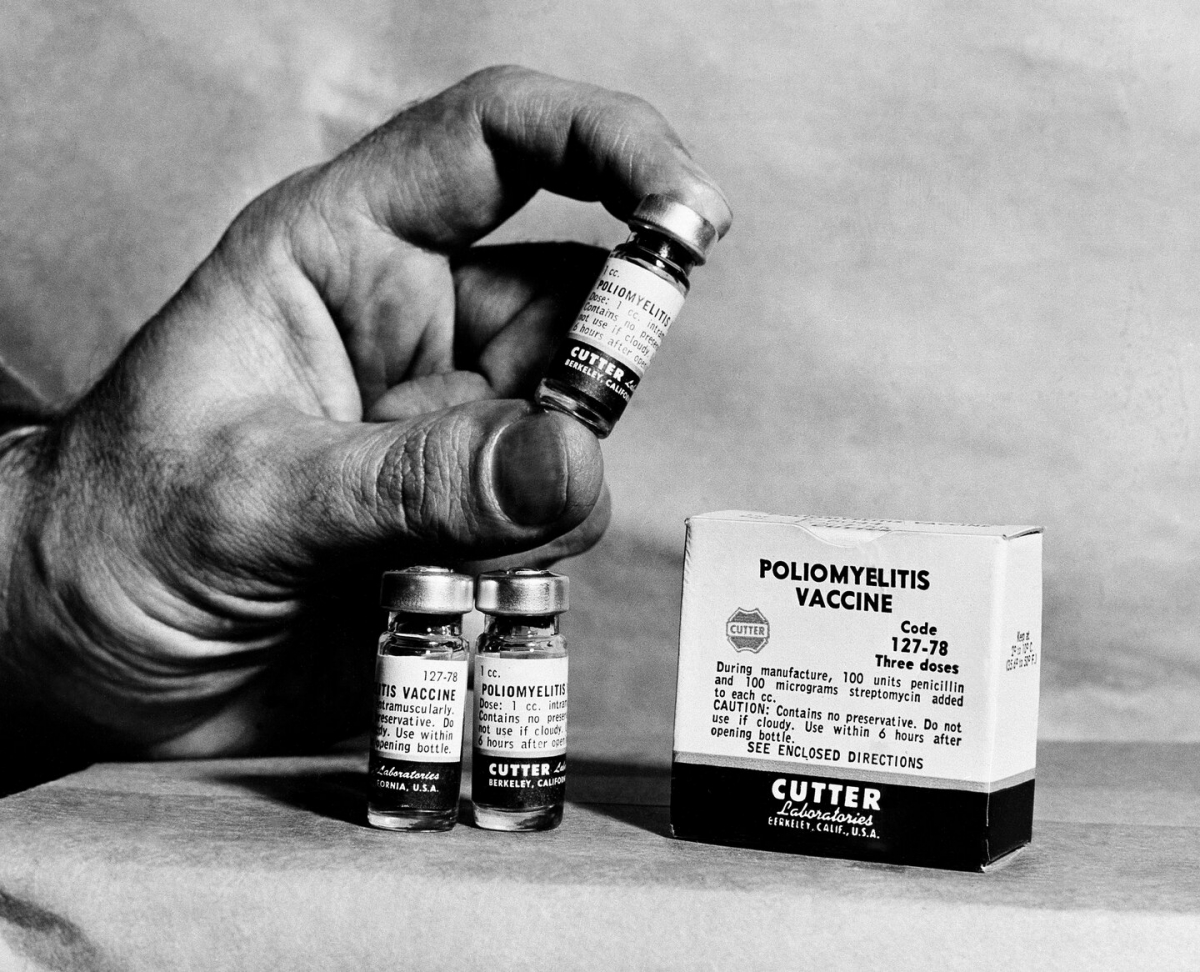

That same day, licenses were hurriedly granted to several drug companies, including Cutter Laboratories, to make the vaccine.

But the officials granting the licenses were never told of Eddy’s findings, Offit wrote.

AD The year before, Eddy’s scrutiny of the Cutter vaccine had continued through the summer and fall.

It must have been a difficult time. She was 52. Her husband, Jerald Guy Wooley, 64, a fellow National Institutes of Health scientist, had died suddenly the previous April, leaving her with three daughters, two of them still at home in Bethesda, according to his obituary. Her mother moved in to help out.

Eddy was born in 1903 in Glen Dale, W.Va., a small town on the Ohio River, south of Wheeling, according to a 1985 biographical sketch by Elizabeth Moot O’Hern. Her father was a doctor.

She had started at NIH in 1937, had headed testing of vaccines for influenza, and in 1954 was asked to help test the Salk polio vaccine. The pressure was intense. “For weeks she and her staff worked around-the-clock, seven days a week,” O’Hern wrote.

AD “This was a product that had never been made before, and they were going to use it right away,” Eddy had said.

She began testing Cutter’s samples in August 1954 and continued through November, according to a later report in the Congressional Record. She found that three of the six samples paralyzed test monkeys.

“What do you think is wrong with these monkeys?” she asked a colleague, Offit recounted.

“They were given polio,” the colleague replied.

“No,” Eddy said. “They were given the … vaccine.”

Eddy’s discovery suggested that Cutter’s manufacturing process was flawed. Its vaccine should have contained only killed virus.

She reported her findings to William Workman, head of the NIH Laboratory of Biologics Control.

But amid the scientific and bureaucratic chaos, Workman never told the licensing committee, Offit wrote.

AD Starting on the evening of April 12, 1955, batches of the Salk vaccine made by five drug firms were shipped out in boxes marked “POLIO VACCINE: RUSH.”

About 165,000 doses of Cutter’s went out.

Within weeks, reports of mysterious polio infections started coming in.

On April 27, 7-year-old Susan Pierce of Pocatello, Idaho, died of polio about a week after getting the Cutter vaccine. She had been in an iron lung for nine days when she succumbed. Her brother Kenneth had been vaccinated at the same time, but he was okay.

Other cases followed.

Alton Ochsner, a professor of surgery at Tulane Medical School and founder of the Ochsner Clinic in New Orleans, gave the vaccine to his grandson Eugene Davis, Offit wrote. The child died May 4.

Not only did some people injected with the tainted vaccine get sick, but some who got the vaccine went on to infect family members and neighbors.

AD On June 5, 1955, 33-year-old Annabelle Nelson of Montpelier, Idaho, died of polio after her two children had been given the vaccine in April, according to news reports at the time.

The government ordered the Cutter vaccine withdrawn on April 27. But damage had been done.

“By April 30, within forty-eight hours of the recall,” Offit wrote. “Cutter’s vaccine had paralyzed or killed twenty-five children: fourteen in California, seven in Idaho, two in Washington, one in Illinois, and one in Colorado.”

On May 6, all polio vaccinations were postponed. They were resumed on May 15 after the government had rechecked the vaccines for safety. But people were still frightened.

Offit recalled his mother asking their doctor: “What’s the story? Should we be getting this vaccine or not?"

Eventually, he was vaccinated when he was about 6 years old.

Years later, in a suit brought against Cutter, the firm was found not negligent in making its vaccine because it had done its best making a new drug that was complicated to produce.

But it was found financially liable for the calamity it had caused during that spring of 1955.

The jury foreman said: “Cutter Laboratories [brought] to market a … vaccine which when given to plaintiffs caused them to come down with polio.”

Source:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2020/04/14/cutter-polio-vaccine-paralyzed-children-coronavirus/